Border Crossings

Painting for a New Era

Robert C. Morgan

In the regulated frontier of today’s surveillance between borders, crossing from one place to another is less innocent than it used tobe. Now we are required to have identity papers on hand, to remove our shoes and belts, to dispose liquids from our luggage, to be fingerprinted, and even detained for further investigation, depending on what borders we are attempting to leave or enter. A certain degree of peril may be involved. Yet even if there is no obvious peril, we may still feel vulnerable. We have learned to stay alert to what is happening around us. While we may regard these security measures as only political, they also relate to the way one thinks about being an artist. It would appear that serious artists spend much of their time crossing borders in order to get from one place to another in order to understand what they are doing. There is a certain risk in doing this, a sense of doubt, even a feeling of trepidation. Whether politically or aesthetically, to travel from what is known to what is unknown is as much political as it is aesthetic. It is part of the era in which we live and work. It is related to our everyday anxieties, and therefore implicitly related to the content of recent abstract art, which, of course, includes abstract painting.

In the regulated frontier of today’s surveillance between borders, crossing from one place to another is less innocent than it used tobe. Now we are required to have identity papers on hand, to remove our shoes and belts, to dispose liquids from our luggage, to be fingerprinted, and even detained for further investigation, depending on what borders we are attempting to leave or enter. A certain degree of peril may be involved. Yet even if there is no obvious peril, we may still feel vulnerable. We have learned to stay alert to what is happening around us. While we may regard these security measures as only political, they also relate to the way one thinks about being an artist. It would appear that serious artists spend much of their time crossing borders in order to get from one place to another in order to understand what they are doing. There is a certain risk in doing this, a sense of doubt, even a feeling of trepidation. Whether politically or aesthetically, to travel from what is known to what is unknown is as much political as it is aesthetic. It is part of the era in which we live and work. It is related to our everyday anxieties, and therefore implicitly related to the content of recent abstract art, which, of course, includes abstract painting.

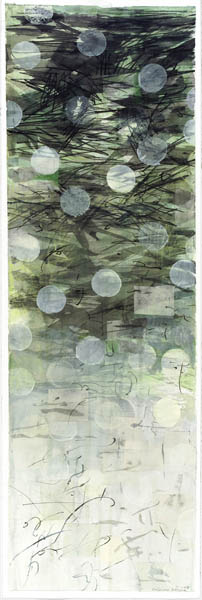

Keiko Hara, the instigator of the exhibition, is an artist who has worked and taught for many years in the United States. Although she has developed a career outside of her native Japan, her paintings retain the signs directly related to her indigenous culture. Keiko’s brush carries significance in the sense that the formal attributes of painting do not end in either technique or decoration, but in their ability to transform her calligraphy into expressive painterly marks. In this way, she communicates a spiritual awareness of things in nature, which is an omnipresent concern in Eastern painting. In her series of Sumi ink, gouache, graphite, collage, and mixed media works on paper, entitled Verses (2008), she reveals not only the density of writing, as in the Western notion of the palimpsest, but also her reflections on nature. The spectrum of these two themes may be compared as we look at Verses 1,2, and 4 in comparison with Verses 8, 9, and 11. While all of Keiko’s works are presented in a unified vertical format, the distinction between these two random groups is worth noting. In the first, the “white” writing used in Verses 4 suggests a simultaneous gravity and transcendence of the surface. The overlay of whiteness creates a luminous effect closely related to Verses 1 and 2 in which small Sumi ink marks appear. In the second group, the paintings suggest intimate memories of nature, as in Verses 9, where the reflections of light bouncing off the water communicate a Buddhist feeling of “emptiness” derived through perception, contemplation, and the extended distillation of memory.

Donald Groscost’s oil paintings on aluminum, canvas, and paper display an indelible consistency in their remarkable restraint and formal virtuosity. While Keiko’s paintings move between being present with nature, yet absent within it, the American, Groscost is involved with nature through simulation. He seems to be transforming the appearance of the landscape from the historical past by presenting a completely different point of view. The artist’s vivid style of painterly manipulation-- more activated, visceral, and varied than the static techniques used by the Hudson River School painters of the nineteenth century for example -- conjoins with intensely overlapping rhythmic forms and colors. In doing so, he literally re-invents the American landscape. His perception of nature is neither present nor absent. Rather it goes in the direction of transforming the way we perceive the natural world, not through technological interference or its consequential detritus, but through envisioning a possibility where representation and abstraction declare a new visual structure. They flip back and forth, slightly reminiscent of the Surrealist paintings of Max Ernst in the early forties. Even so, Groscost is very much on his own trajectory. The intimacy of these paintings sparkles with light and warmth. They are not detached from nature, but intrinsically close to it. His confidence in rendering the sublime suggests a new source of content. In the future, the representation of nature may be difficult to recognize without a clear re-envisioning of the landscape as the source of its continuity.

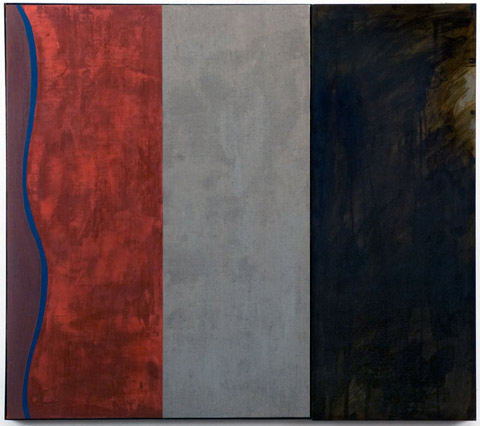

Rene Pierre Allain is a French-Canadian painter who works with pigments and acrylic paint in relation to such diverse materials as plaster, linen, wood, steel and gun blue. For years, his large welded steel frames contained minimal panels of monochrome color. By 2001, he began opening up the panels, initially with straight lines, then groupings of small discs, then partial  camouflage patterns, and – in his recent “Modifier” series – with textural brushwork and wavy vertical lines. It would appear that the earlier emblematic quality in Allain’s work has given way to painting as a kind of self-conscious act. While he employs signs that may allude to expressionist content, there is, in fact, no expressionist content. This further suggests that not all content in abstract painting is expressionist. Somehow, this point seems essential when viewing Allain’s work, especially in the “Modifiers” (2008). The use of bright and dark color and the separations between the panels play heavily on the act of perception. In the context of Keiko Hara and Donald Groscost, I would hesitate to say that Allain is entirely removed from nature. Rather his position represents a third voice in the exhibition. Where Keiko moves between presence and absence in her painterly inscriptions, and Groscost simulates natural phenomena through the act of painting, Allain’s painting simply confronts nature with his tendency to heighten the act of perception. As the world appears more complex in testing the limits of the virtual in terms of tactile reality, Allain brings this reality close to the forefront.

camouflage patterns, and – in his recent “Modifier” series – with textural brushwork and wavy vertical lines. It would appear that the earlier emblematic quality in Allain’s work has given way to painting as a kind of self-conscious act. While he employs signs that may allude to expressionist content, there is, in fact, no expressionist content. This further suggests that not all content in abstract painting is expressionist. Somehow, this point seems essential when viewing Allain’s work, especially in the “Modifiers” (2008). The use of bright and dark color and the separations between the panels play heavily on the act of perception. In the context of Keiko Hara and Donald Groscost, I would hesitate to say that Allain is entirely removed from nature. Rather his position represents a third voice in the exhibition. Where Keiko moves between presence and absence in her painterly inscriptions, and Groscost simulates natural phenomena through the act of painting, Allain’s painting simply confronts nature with his tendency to heighten the act of perception. As the world appears more complex in testing the limits of the virtual in terms of tactile reality, Allain brings this reality close to the forefront.

Upon seeing the work of these artists together one might say that borders are being crossed by all three, and in the process the signifying properties of abstract painting are being re-invented. Again, nature comes to the forefront of our attention (as always) through the internalization of our perceptions.

Robert C. Morgan is a writer, painter, international critic, and curator. He holds a doctorate in contemporary art and aesthetics from New York University and currently teaches at the School of Visual Arts in New York.